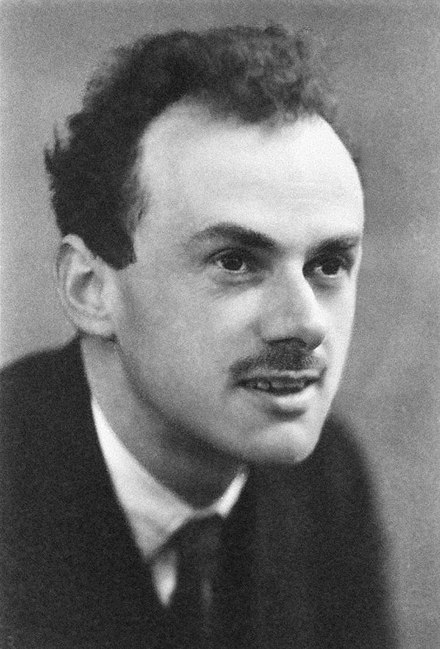

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac OM FRS; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English theoretical physicist who made fundamental contributions to the early development of both quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a member of the Center for Theoretical Studies, University of Miami, and spent the last decade of his life at Florida State University.

Among other discoveries, he formulated the Dirac equation which describes the behaviour of fermions and predicted the existence of antimatter. Dirac shared the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics with Erwin Schrödinger "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory". He also made significant contributions to the reconciliation of general relativity with quantum mechanics.

He was regarded by his friends and colleagues as unusual in character. Albert Einstein said of him "This balancing on the dizzying path between genius and madness is awful".

He is regarded as one of the most significant physicists of the 20th century. Wikipedia, Paul Dirac

Paul Dirac wasn't just a brilliant theoretical physicist; he was a man whose very presence sparked fascination and bewilderment. Often referred to as “the strangest man in the world” by his colleagues, this title was coined by Niels Bohr, who had the privilege—and challenge—of working with Dirac. Their relationship, initially professional, eventually blossomed into a human bond marked by moments that only someone like Dirac could inspire.

Dirac’s brilliance wasn’t just in his groundbreaking contributions to physics, but in his extraordinarily peculiar approach to life itself. His communication style was as precise and unembellished as his theories. Niels Bohr, struggling to complete a scientific paper, once confessed, “I don’t know how to go on.” Dirac, ever the purist in logic, responded coldly, “I was taught in school that you should never start a sentence without knowing the end.”

And this stark, almost robotic demeanor wasn’t limited to his work. At one dinner, a fellow guest casually remarked, “Nice evening, isn’t it?” Dirac, without missing a beat, stood up, walked to the window to check the weather, and returned with the uncharacteristically succinct reply: “Yes.”

But it was his social awkwardness that painted him as the quintessential oddball. At a Copenhagen party, Dirac proposed a theory on the optimal distance from a woman’s face at which it appears most attractive—backed by his own research, of course. His response to a curious colleague’s question about his personal experience was both absurd and perfectly Dirac: “About that close,” he said, holding his palms about a meter apart.

Then there was the famous incident at the University of Toronto, when, after delivering a lecture, he was asked a question by a student. Dirac’s response? “This is not a question, it is an observation. Next question, please.”

Yet, despite all his brilliance, Dirac's discomfort with philosophy, literature, and even religion was profound. He dismissed poetry as “saying something that everyone already knows in words no one can understand” and offered a scathing critique of religion, claiming that scientists must acknowledge its absurdity. In Dirac’s worldview, God may have used extraordinary mathematics to create the universe, but it was Dirac who, humorously, became known as "His prophet," according to his contemporary Wolfgang Pauli.

In every moment, Dirac's life seemed to blur the line between genius and eccentricity, leaving those who encountered him to wonder: was he a physicist of the highest order, or simply the strangest man to ever walk the earth?

Freeman Dyson

"For theoretical physicists, I would say the problem is to read God's mind. He's very sophisticated. His idea of what's beautiful isn't always the same as ours. I think Dirac's method can be extremely misleading. Dirac maintained that the way to make discoveries in physics was to look for something beautiful, but I think it led him very badly astray. First of all, his great discovery, the Dirac equation, wasn't in fact done that way, although he afterwards maintained that it was. He invented the philosophy of the beautiful post partum. If you look at what he actually wrote at the time, it's clear he was heavily guided by the experiments. And afterwards, when he adopted this philosophy of the beautiful, he stopped making discoveries. It's sad that it didn't work. It didn't work for Einstein, either. Einstein had the same philosophy of the beautiful in later life, and it led him astray, too. The more brilliant you are, the more badly you get led astray." [Freeman Dyson]

He unlocked the secrets of antimatter—then spent his Saturdays chopping wood in the forest like a lumberjack.

Princeton, New Jersey. A crisp Saturday morning in 1962.

If you'd been walking the wooded trails near the Institute for Advanced Study, you might have seen something strange: a thin, quiet man in his sixties, carrying an axe over his shoulder, methodically splitting logs and clearing paths.

You'd never guess you were watching one of the most brilliant physicists who ever lived.

His name was Paul Dirac. And by that Saturday morning, he'd already changed the universe.

At just 31 years old, Dirac had become the youngest theoretical physicist ever to win the Nobel Prize. He'd formulated the Dirac equation—a mathematical breakthrough that predicted the existence of antimatter decades before scientists could prove it existed.

Antimatter. The mirror image of ordinary matter. The stuff of science fiction that turned out to be science fact.

Dirac discovered it with mathematics alone, sitting at a desk, working through equations that described how electrons behave at the quantum level. When he finished, the math told him something impossible: there should be particles with the opposite charge of electrons.

Positrons. Antimatter.

Other physicists thought he'd made a mistake. The equations must be wrong. Antimatter couldn't exist.

Four years later, in 1932, Carl Anderson discovered positrons in a cloud chamber experiment. Dirac had been right. He'd predicted the existence of something nobody had ever seen, using nothing but equations.

That's the kind of mind Paul Dirac had. He could see truths about reality that were invisible to everyone else, hidden in the structure of mathematics itself.

His work laid the foundation for quantum mechanics and particle physics. He fundamentally reshaped how we understand the universe at its smallest scale. Einstein called him "the most beautiful mind." Oppenheimer said Dirac's equations had "a kind of inevitability and beauty."

This was a man who stood alongside Einstein, Heisenberg, and Schrödinger as one of the architects of modern physics.

And on weekends, he chopped wood.

Not as a hobby. Not as exercise. As something deeper.

Dirac was famously silent. He spoke so rarely that colleagues invented a unit of measurement: the "dirac"—defined as one word per hour. He could sit through entire dinners without saying anything. He attended social events and stood perfectly still, observing, saying nothing.

He wasn't rude. He simply didn't speak unless he had something precise to say. And most of the time, he didn't.

But in the woods, with an axe, he found something he couldn't find anywhere else: clarity.

Colleagues at Princeton would occasionally join him on his walks. They'd watch him work—swinging the axe with methodical precision, splitting logs with the same careful attention he gave to equations. He'd clear fallen branches from trails, stack wood, move through the forest with quiet purpose.

He rarely spoke during these walks. But observers said he seemed completely absorbed, as if the physical act of chopping wood helped him think.

And it did.

Dirac once explained that he preferred activities where his hands were occupied but his mind was free. Walking. Chopping wood. Physical work that required just enough attention to quiet the noise of everyday thought, but not so much that he couldn't think deeply about physics.

This wasn't procrastination. This was his method.

While other physicists filled their weekends with conferences, lectures, and academic socializing, Dirac disappeared into the woods. While others debated quantum mechanics in faculty lounges, Dirac split logs in silence.

And somehow, that solitude and physical work produced some of the most elegant physics ever conceived.

There's something profound about this image: the man who discovered antimatter, spending his Saturdays like a nineteenth-century frontiersman, alone in the forest with hand tools.

It reveals something we often forget about genius: brilliance doesn't happen only at desks and blackboards. Sometimes it happens in the spaces between formal work. In the rhythm of physical labor. In the quiet of nature.

Dirac understood something modern neuroscience is only now confirming: the brain solves problems when you're not actively trying. The "default mode network"—the part of your brain that activates when you're not focused on any specific task—is where creative insights happen.

Walking in the woods. Swinging an axe. Letting your mind wander.

That's when breakthroughs occur.

Dirac spent decades at Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study, where he worked alongside Einstein, Gödel, Oppenheimer, and von Neumann—arguably the greatest concentration of genius in human history.

Einstein played violin. Gödel took long walks with Einstein, discussing philosophy. Oppenheimer rode horses.

Dirac chopped wood.

Each found their own way to think. Their own method of giving their minds space to work on problems too complex for conscious thought.

But here's what makes Dirac's story particularly striking: he was so profoundly uncomfortable with fame, with recognition, with being celebrated, that he almost declined the Nobel Prize.

He told colleagues he didn't want it. The attention would be unbearable. The speeches, the ceremonies, the public acknowledgment—all of it horrified him.

His colleagues convinced him to accept by pointing out that refusing would create even more attention.

So he went to Stockholm in 1933. He accepted the Nobel Prize with a speech so brief and understated that it became legendary. Then he returned to his quiet life, his equations, and his walks in the woods.

He never sought fame. Never promoted himself. Never played the academic politics that others used to build careers.

He just worked. And walked. And chopped wood.

By the 1960s, younger physicists would visit Princeton hoping to meet the legendary Dirac. They'd heard about his equations, his Nobel Prize, his discovery of antimatter.

They'd find him in the woods, axe over his shoulder, saying nothing.

Some were disappointed. They expected grand pronouncements, profound wisdom delivered in lecture format.

But the physicists who understood—who really understood—saw something different: a man who'd achieved everything possible in his field and found peace not in recognition, but in simplicity.

Dirac lived until 1984. He died at 82, having spent more than half a century as one of the most respected physicists alive.

When people asked him about his greatest achievement, he rarely mentioned antimatter or quantum mechanics.

He talked about clarity. About the beauty of mathematical equations. About finding solutions that felt inevitable, as if they'd always existed and he'd simply discovered them.

He talked, occasionally, about the importance of walking.

Today, physics students learn the Dirac equation in their first quantum mechanics courses. They study his prediction of antimatter. They work through his mathematical formulations that describe the fundamental behavior of particles.

But most of them never hear about the woods. The axe. The Saturday mornings spent in silence, thinking while working.

That part of his story doesn't fit neatly into textbooks. It doesn't have equations. It can't be tested or proven.

But it might be the most important part.

Because it reveals a truth about how great work actually happens: not through relentless focus and constant effort, but through balance. Through giving your mind space to wander. Through connecting abstract thought to physical action.

Dirac proved that genius doesn't have to be flashy, loud, or performative. It can be quiet. Patient. Grounded in simple routines that create space for extraordinary thinking.

He was the man who discovered that every particle has a mirror image made of antimatter. That reality is stranger and more symmetric than anyone imagined. That the universe operates according to mathematical principles of profound elegance.

And he figured much of it out while splitting logs in a New Jersey forest, saying nothing, thinking everything.

That's not a contradiction. That's the method.

Sometimes the path to understanding the universe runs straight through the woods, with an axe over your shoulder and silence in your mind.

Paul Dirac knew that. He lived it for decades.

And on a crisp Saturday morning in 1962, if you'd been walking those Princeton trails, you could have seen it for yourself: genius with an axe, thinking about antimatter while splitting wood, completely at peace.

Dirac was the strangest man who ever visited my institute. During one of Dirac’s visits I asked him what he was doing. He replied that he was trying to take the square-root of a matrix, and I thought to myself what a strange thing for such a brilliant man to be doing. Not long afterwards the proof sheets of his article on the equation arrived, and I saw he had not even told me that he had been trying to take the square root of the unit matrix! [Bohr]

See Also

Bearden - Precursor Engineering: Via Tickling of the Dirac Sea Vacuum

Dirac equation

Dirac Sea

ether

Russell to NYT - 1930 November 2

Schrodinger equation